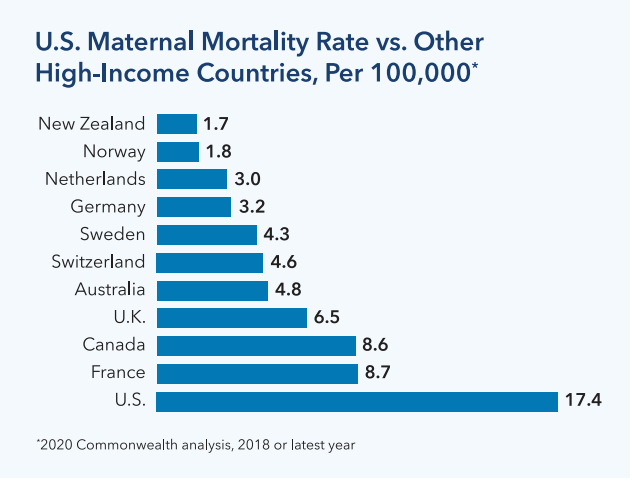

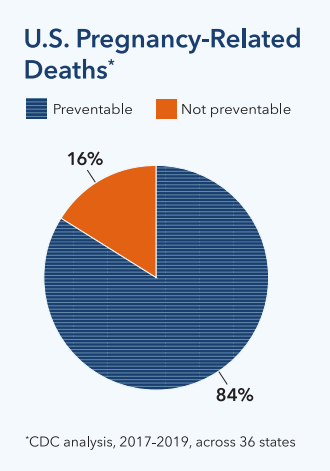

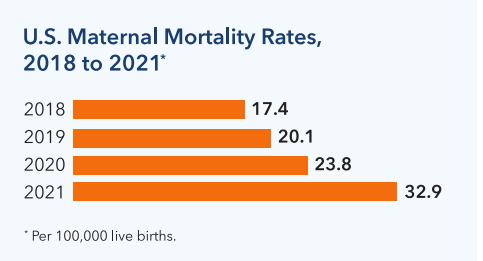

In the U.S, too many women are dying prematurely during and after childbirth, and the problem is worsening.1 This policy brief provides an overview of maternal health challenges, ethnic and racial disparities, and the multifactorial drivers causing disparities in maternal health outcomes. Maternal mortality rates in the U.S. are higher than in other high-income countries.2 Most maternal deaths are preventable. 3

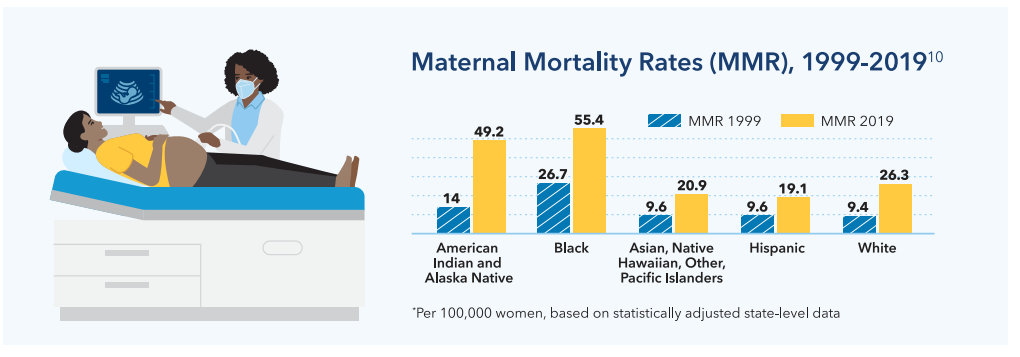

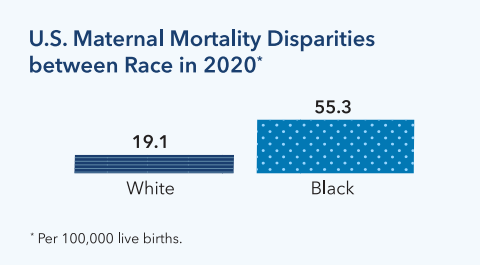

In 2020, maternal mortality rates were nearly 3 times higher for Black women than white women (55.3 vs. 19.1).4 While the COVID-19 pandemic limited access to care, worsening maternal mortality, increases in maternal death rates began prior to the start of the pandemic.5

Contributing Factors

Most maternal deaths, and racial/ethnic disparities in deaths and other maternal outcomes, are preventable. The drivers of maternal health disparities are complex and multifactorial, related to structural and systemic racism and experiences of discrimination, all of which are associated with increased risks for health problems during and after pregnancy.11

Housing and physical environment: Redlining and continued housing segregation has led many pregnant people of color and new mothers to reside in communities with higher rates of crime, interpersonal violence, instability, pollution, and other stressors. Preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication, has been linked to environmental contaminants in places where people of color often live and work.12,13

Economic stability: Economic inequality and racial wealth gaps continue to persist and contribute to health disparities. Black women often face limited economic opportunities and high stress levels, which worsens maternal health outcomes.14,15

Food insecurity: Research confirms that poor nutrition during pregnancy, common among people with lower incomes, is associated with poor birth outcomes.16,17

Health care access: People of color are more likely to be uninsured and to face challenges to obtaining care, including limited access to culturally and linguistically matched providers and hospitals. Health care coverage before, during, and after pregnancy supports positive maternal and infant outcomes during and after childbirth.18

Care quality: Research on maternal mortality cases and near misses among women of color have demonstrated that physicians are sometimes nonresponsive to patient needs or slow to respond. Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic women reported higher levels of mistreatment.19,20

Racism and discrimination: Other experiences of racism and discrimination can contribute to chronic stress and lead to poor health outcomes as well.21 A Black mother with a college-level education is 60% more likely to die in childbirth than a White or Hispanic woman with less than a high school diploma.22 These racial disparities exist across all educational levels.23

Public Policy

Kaiser Permanente supports the following policies that can improve maternal health care and outcomes and reduce disparities:

Improve access to comprehensive health insurance coverage at both the federal and state level: To promote access to high-quality care, policymakers should support the extension of Medicaid and CHIP coverage to 12 months postpartum and streamline enrollment and eligibility verification. They should also expand Medicaid and commercial subsidies to everyone that meets eligibility criteria, regardless of immigration status.

Improve quality and systems of care: Support demonstration projects to evaluate the impact of virtual care modalities (telephone or video visits) on reducing health disparities in prenatal and postpartum care. Include remote patient monitoring programs that promote early and regular prenatal care and help identify and manage risk factors.

Support research, education, and training: Invest in culturally responsive programs, initiatives, and demonstration that improve public awareness of common pregnancy complications, and provide implicit bias trainings for health care providers and staff to reduce care inequities. Explore increased use of paraprofessionals, such as patient navigator and community health workers, to improve care and outcomes.

Support access to evidence-based telehealth services and virtual care, to make access convenient and easy: Support expanded access to telehealth and remote monitoring services, through telehealth coverage policies, expansion of broadband service to unserved and underserved areas, and subsidized internet and device access for patients with low incomes.

Support policies that enable payers and providers to address unmet social needs that profoundly affect patients’ health, including food insecurity and poor nutrition, housing, and environmental hazards. Through policy change, leaders can ensure a high-quality, equitable continuum of care that optimizes the health and well-being of all mothers and babies. Policies can also improve underlying factors that impact pregnant people’s health, including socioeconomic status, access to care, access to food and housing, and the physical environment, so that the overall risk of maternal illness and deaths are reduced.

References

- Laura Ungar, “Maternal Deaths in the U.S. More Than Doubled Over Two Decades, Black Mothers Died at the Highest Rate,” Associated Press, July 3, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/black-maternal-mortality-american-indian-hispanic-deaths-64da18fec80f8f1790aee2e9986a757e.

- Roosa Tikkanen, et al., “Maternal Mortality and Maternity Care in the United States Compared to 10 Other Developed Countries,” The Commonwealth Fund, November 18, 2020,https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries#:~:text=Key%20Findings%3A%20The%20U.S.%20has,mortality%20rate%20among%20developed%20countries..

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 States, 2017-2019,” September 19, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html.

- Laura Fleszar, “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, 330(1):52-61, 2023, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2806661?resultClick=1.

- Laura Fleszar, “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, 330(1):52-61, 2023, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2806661?resultClick=1.

- Laura Fleszar, “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, 330(1):52-61, 2023, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2806661?resultClick=1.

- Laura Fleszar, “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, 330(1):52-61, 2023, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2806661?resultClick=1.

- Laura Fleszar, “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, 330(1):52-61, 2023, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2806661?resultClick=1.The data from this study is based on statistically adjusted, aggregated state data for all states by race and ethnicity, to allow comparisons over time and across states where terminology and data collection approaches sometimes differed.

- DL Hoyert, “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020” National Center for Health Statistics E-Stats, February 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/E-stat-Maternal-Mortality-Rates-2022.pdf

- DL Hoyert, “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021,”National Center for Health Statistics, March 16, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.htm#Table.

- L Hill, S Artiga, U Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” KFF, Nov. 1, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.

- JG Katon, DA Enquobahrie, K Jacobsen, LC Zephyrin, “Policies for Reducing Maternal Morbidity and Mortality and Enhancing Equity in Maternal Health,” The Commonwealth Fund, Nov. 16, 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/nov/policies-reducing-maternal-morbidity-mortality-enhancing-equity.

- M Gochfeld and J Burger, “Disproportionate Exposure in Environmental Justice Populations: The Importance of Outliers,” American Journal of Public Health, Dec. 2011, 101(Suppl1), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3222496/.

- Benjamin Harris and Sydney Schreiner Wertz, “Racial Differences in Economic Security: The Racial Wealth Gap,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 15, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/racial-differences-economic-security-racial-wealth-gap.

- D Vilda, M Wallace, L Dyer, E Harville, and K Theall, “Income Inequality and Racial Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the U.S.” Population Health, Dec. 9, 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6734101/.

- Y Zhu, MM Hedderson, S Sridhar, et al. Poor Diet Quality in Pregnancy is Associated with Increased Risk of Excess Fetal Growth: A Prospective Multi-Racial/Ethnic Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(2):423-432.

- Y Zhu, SF Olsen, P Mendola, et al. Maternal Consumption of Artificially Sweetened Beverages During Pregnancy, and Offspring Growth through 7 Years of Age: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(5):1499- 1508.

- L Hill, S Artiga, U Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” KFF, Nov. 1, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.

- L Hill, S Artiga, U Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” KFF, Nov. 1, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/

- JC Salughter-Acey, S Sealy-Jefferson, L Helmkamp, C Caldwell, et al. “Racism in the Form of Micro-Aggressions and the Risk of Preterm Birth Among Black Women, Annals of Epidemiology, V26(1), January 2016, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1047279715004238.

- L Hill, S Artiga, U Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” KFF, Nov. 1, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.

- E Declercq, LC Zephyrin, “Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer,” The Commonwealth Fund, December 16, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-brief-report/2020/dec/maternal-mortality-united-states-primer.

- L Hill, S Artiga, U Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” KFF, Nov. 1, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.